For all the risky adventures Bran Ferren has chased in the past six decades—a list that includes a variety of hazardous undertakings, from traveling through Afghan war zones to working in Hollywood—there was one highly perilous pursuit he never dared take on: parenthood. “Having a family,” Ferren says, “wasn’t a priority.”

It’s a late-summer afternoon, and Ferren—celebrated inventor, technologist, former head of research and development for Disney’s Imagineering department—is sitting inside a guesthouse-slash-storage facility on his ample East Hampton, New York, spread, drinking his third or fourth Diet Coke of the day. He’s 61 years old and towering, with a wily-looking red-gray beard and dressed in his everyday uniform of khaki pants, sneakers, and a billowy polo shirt. Ferren is the cofounder and chief creative officer of Applied Minds, a world-renowned tech and design firm whose on-the-record customer list includes General Motors, Intel, and the US Air Force; before that he worked on everything from Broadway shows to theme park rides.

But today Ferren is focused on his most important client: his 4-year-old daughter, Kira, who is just a few yards away, traipsing across the garden with a pal. Several years ago, when Ferren was still in his midfifties—a time when many men are easing into their grandfather phase—his partner of more than 25 years, Robyn Low, told him that if he ever wanted to have a kid, the time was now. Finally having a child became a priority, and in 2009 Kira was born.

It took Ferren a while to adjust to fatherhood. He had to scale back on the hazardous work trips, and he had to curtail some of his more treacherous leisure activities, like racing motorcycles and flying helicopters. “I thought, what will it be like for my daughter if I end up becoming a cripple or dropping dead, doing something like that when she’s 4 years old? It changes your perspective.” The sacrifices, though, are worth it. “Everyone says, ‘Well, you’ve never felt love like this before,’” Ferren says. “It turns out to all be absolutely correct.”

Bran Ferren

Art Streiber

We leave the guesthouse and take a stroll around the grounds, where everywhere you turn there’s a project Ferren has initiated on his daughter’s behalf. On one side there’s a wood-shingled pod with a DeLorean-style door, which will serve as Kira’s playroom-slash-study area. (“The idea is that it’ll be a place for her to play until she’s old enough to date,” he says. “At which point we’ll fill it with concrete and roll it into the pond.”) Nearby is a studio where he’s recording a series of interviews with some of his artist and designer friends in hopes that Kira will learn from them years from now. “One of the things about having a kid when you’re older is that you’re not going to see her through a lot of her life,” he says. “So what are the ideas and conversations that I might not get to have with her but that I’d like for her to think about?”

Given Ferren’s age—he’ll be in his midseventies by the time Kira’s ready for college—it makes sense that he’d want to leave some sort of words of wisdom for her. But he also wants to start teaching her about the world now, while they are both still young enough to explore it. “I’ve loved watching my daughter learn about life,” he says. “There’s a big world out there, and I’ve seen only a portion of it.”

All parents obsess over the kind of life they want for their children, but Ferren is actually trying to design one. He’s inspired in part by his own parents, who encouraged him to examine the world around him. They took him to the Pantheon when he was only 7, they let him take apart machines to see how they worked, and they raised him in an environment with paintings and books and records at every turn. “I remember as a kid being shocked when I visited a friend’s house and it wasn’t filled with art,” he says.

Kira Ferren

Art Streiber

Ferren is trying to create the same environment for Kira—one of constant, boundless learning. But he is not the type to simply buy her a globe and a few reference books. Ferren is a man who builds things—huge, intricate, brazenly theatrical things. Fittingly, he has embarked on a childhood-enrichment project so lavish, ornate, and over-the-top it makes even the most aggressive tiger mom seem tame.

In the ’80s and ’90s, Ferren scouted locations for Hollywood features and documentaries in places like Death Valley and Alaska. Around the same time, he was also helping ABC develop some of its location trucks. As a result, he became enamored with off-road expedition vehicles. They were well suited for his many hobbies, including archaeology, mapping, and fine-art nature photography. He built one himself, which he called the MaxiMog, completing it in 2001. Adapted from a Mercedes-Benz all-terrain truck called the Unimog, the vehicle was equipped with videoconferencing equipment and a 40-foot mast with a camera that allowed passengers to see the terrain ahead. (An attachable trailer, meanwhile, featured a collapsible sleeping loft and an espresso machine.) A combination of rugged pragmatism and sleek design, the MaxiMog was eventually displayed at the New York Museum of Modern Art.

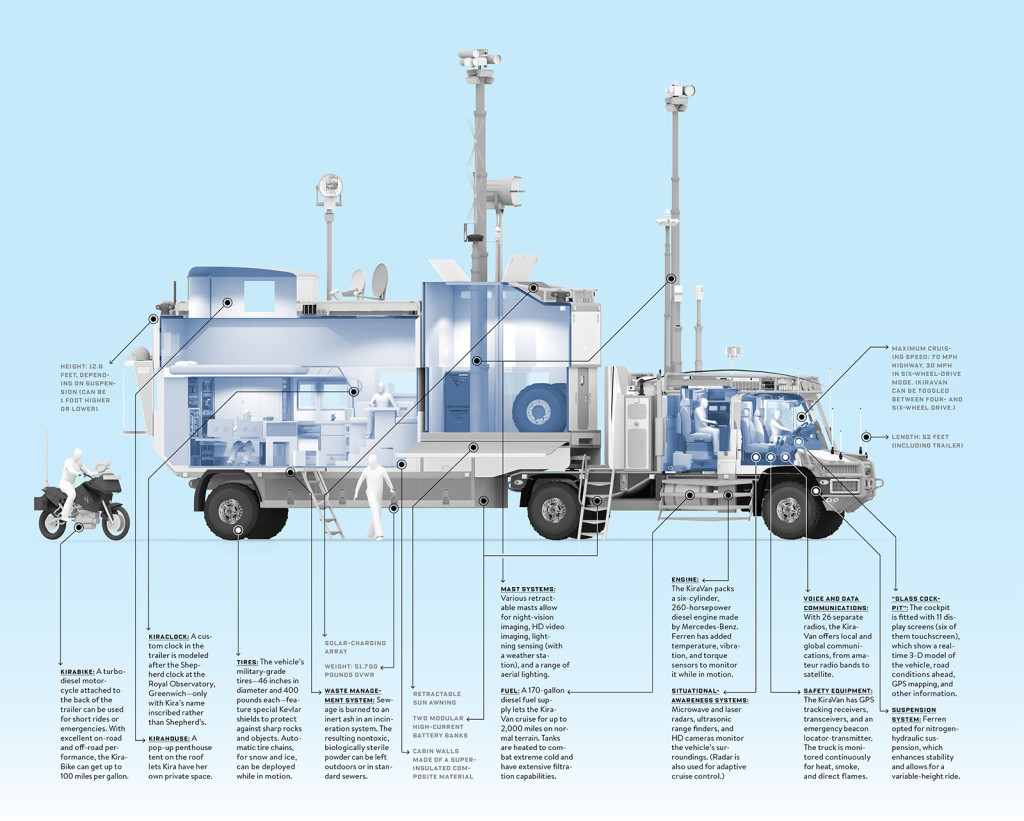

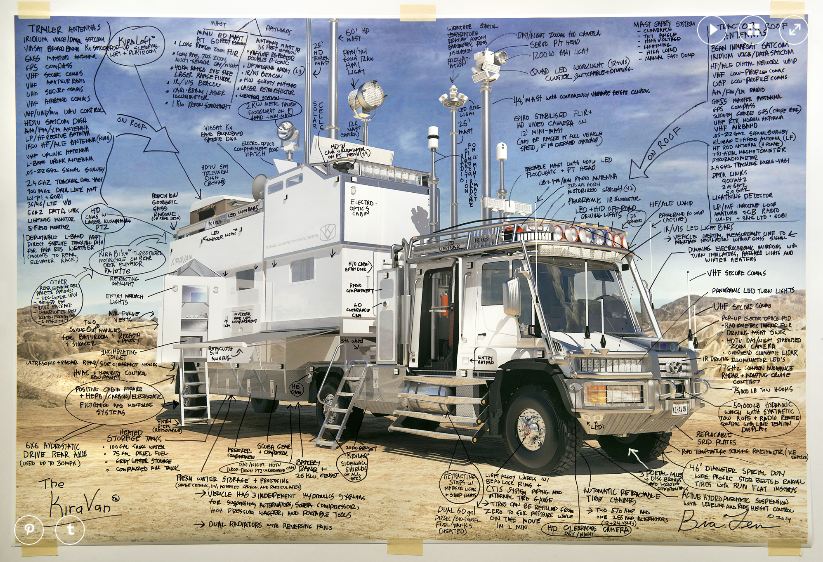

Around the time Kira was born, Ferren had an idea. What if he built an all-new, bigger and better expedition vehicle? No, more than that, what if he made theultimate adventure truck, the very platonic ideal of such a thing—which he could outfit for a family of three? He started to envision a vehicle that could take Kira nearly anywhere on earth without limitation—a mix of high-powered machinery, bomb-shelter self-sufficiency, and luxe-life accoutrements. It would be a mobile, malleable five-star fortress. It could form the centerpiece of his and Kira’s exploration of the world and be her ride into the future. Before he drew up the first blueprints, he’d given it a name: the KiraVan.

Ferren then set out to build the thing, which required dealing with all manner of complicated questions. For example: What materials could he use that would endure both extreme cold and extreme heat? “You’d think it’d be harder to design a jet than an off-road car,” he says. “You’d be wrong. It actually gives you an appreciation for why there are so many shitty cars and why there are so few great anythings. Because, it turns out, to do a great thing is hard.”

To answer the hundreds of questions nagging at him in his quest to build a supertruck, Ferren traveled all over the globe to seek the advice of experts. He spoke with mining consultants to learn how their equipment survives harsh conditions. He picked the brains of oil explorers to find out how their machinery functions over difficult terrain.

Now, nearly four years later, it is almost, sorta, kinda finished, and while Ferren won’t divulge the exact budget of the truck, he grants that its total cost is in the millions. If Ferren’s claims are to be believed, when it finally hits the road sometime this year it will be the most elaborate all-terrain vehicle ever built—a six-wheeled terrestrial spaceship capable of traversing nearly any terrain, from mud-swamped roads to rock-covered pathways to small bodies of water. It will be able to travel up to 2,000 miles without resupply and navigate slopes as steep as 45 degrees—an incline that is difficult to walk up.

Then there are the extras, which include Kevlar-reinforced tires, more than a dozen interlocking communication systems, and a diesel-powered motorcycle “dinghy.” Add to that the KiraVan’s massive trailer, which is 31 feet long and more than 10 feet high and houses an ecofriendly bathroom, a custom-designed upscale kitchen, and Kira’s own “penthouse” loft (which she herself helped design). The only thing missing is a built-in espresso machine. A countertop one will have to do.

Because of his considerable intellectual and financial resources, Ferren can pursue his vision without regard to the usual constraints of time, money, or manpower. And he has. “Bran can go overboard,” says a good friend, former Microsoft CTO Nathan Myhrvold. “Actually, for him, overboard is normal.” In fact, Ferren’s truck is a lot like Ferren himself: unapologetically audacious, highly adaptable, and more than a little extreme.

Bran Ferren

Bran Ferren  Art Streiber

Art Streiber Kira Ferren

Kira Ferren