Category Archives: flotsam

So that’s how the garden hose flooded the yard…

I was working in the basement when I heard the water meter start running full tilt. I was the only one home. From the back porch I saw a big pool of water coming from my garden hose. I caught it all on camera…..

Mini Pix

Slow down!

DUI caught on camera

Bran Ferren

Just finished an article in wired 22.44 about the kira van. It’s an amazing project by Bran Ferren. I had seen his first RV at MOMA about ten years ago. I had no idea that he was working on v2.0

Bran Ferren (born January 16, 1953), is a technologist, artist, architectural designer, vehicle designer, engineer, lighting and sound designer, visual effects artist, scientist, lecturer, photographer, entrepreneur, and inventor. Ferren is the former President of Research and Development of Walt Disney Imagineering[21] as well as founder of Associates & Ferren, a multidisciplinary engineering and design firm acquired in 1993 by Disney. He is Chief Creative Officer of Applied Minds, which he co-founded in 2000 with Danny Hillis.

For all the risky adventures Bran Ferren has chased in the past six decades—a list that includes a variety of hazardous undertakings, from traveling through Afghan war zones to working in Hollywood—there was one highly perilous pursuit he never dared take on: parenthood. “Having a family,” Ferren says, “wasn’t a priority.”

It’s a late-summer afternoon, and Ferren—celebrated inventor, technologist, former head of research and development for Disney’s Imagineering department—is sitting inside a guesthouse-slash-storage facility on his ample East Hampton, New York, spread, drinking his third or fourth Diet Coke of the day. He’s 61 years old and towering, with a wily-looking red-gray beard and dressed in his everyday uniform of khaki pants, sneakers, and a billowy polo shirt. Ferren is the cofounder and chief creative officer of Applied Minds, a world-renowned tech and design firm whose on-the-record customer list includes General Motors, Intel, and the US Air Force; before that he worked on everything from Broadway shows to theme park rides.

But today Ferren is focused on his most important client: his 4-year-old daughter, Kira, who is just a few yards away, traipsing across the garden with a pal. Several years ago, when Ferren was still in his midfifties—a time when many men are easing into their grandfather phase—his partner of more than 25 years, Robyn Low, told him that if he ever wanted to have a kid, the time was now. Finally having a child became a priority, and in 2009 Kira was born.

It took Ferren a while to adjust to fatherhood. He had to scale back on the hazardous work trips, and he had to curtail some of his more treacherous leisure activities, like racing motorcycles and flying helicopters. “I thought, what will it be like for my daughter if I end up becoming a cripple or dropping dead, doing something like that when she’s 4 years old? It changes your perspective.” The sacrifices, though, are worth it. “Everyone says, ‘Well, you’ve never felt love like this before,’” Ferren says. “It turns out to all be absolutely correct.”

Bran Ferren

Art Streiber

We leave the guesthouse and take a stroll around the grounds, where everywhere you turn there’s a project Ferren has initiated on his daughter’s behalf. On one side there’s a wood-shingled pod with a DeLorean-style door, which will serve as Kira’s playroom-slash-study area. (“The idea is that it’ll be a place for her to play until she’s old enough to date,” he says. “At which point we’ll fill it with concrete and roll it into the pond.”) Nearby is a studio where he’s recording a series of interviews with some of his artist and designer friends in hopes that Kira will learn from them years from now. “One of the things about having a kid when you’re older is that you’re not going to see her through a lot of her life,” he says. “So what are the ideas and conversations that I might not get to have with her but that I’d like for her to think about?”

Given Ferren’s age—he’ll be in his midseventies by the time Kira’s ready for college—it makes sense that he’d want to leave some sort of words of wisdom for her. But he also wants to start teaching her about the world now, while they are both still young enough to explore it. “I’ve loved watching my daughter learn about life,” he says. “There’s a big world out there, and I’ve seen only a portion of it.”

All parents obsess over the kind of life they want for their children, but Ferren is actually trying to design one. He’s inspired in part by his own parents, who encouraged him to examine the world around him. They took him to the Pantheon when he was only 7, they let him take apart machines to see how they worked, and they raised him in an environment with paintings and books and records at every turn. “I remember as a kid being shocked when I visited a friend’s house and it wasn’t filled with art,” he says.

Kira Ferren

Art Streiber

Ferren is trying to create the same environment for Kira—one of constant, boundless learning. But he is not the type to simply buy her a globe and a few reference books. Ferren is a man who builds things—huge, intricate, brazenly theatrical things. Fittingly, he has embarked on a childhood-enrichment project so lavish, ornate, and over-the-top it makes even the most aggressive tiger mom seem tame.

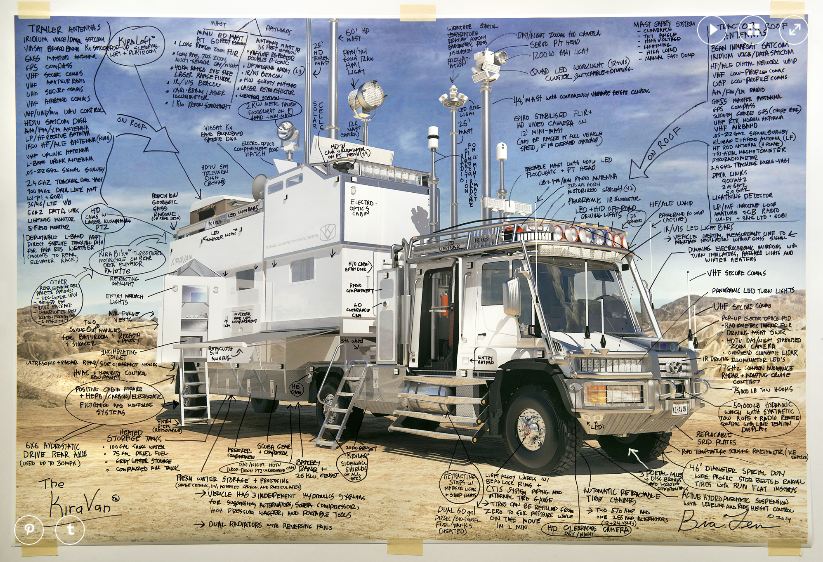

In the ’80s and ’90s, Ferren scouted locations for Hollywood features and documentaries in places like Death Valley and Alaska. Around the same time, he was also helping ABC develop some of its location trucks. As a result, he became enamored with off-road expedition vehicles. They were well suited for his many hobbies, including archaeology, mapping, and fine-art nature photography. He built one himself, which he called the MaxiMog, completing it in 2001. Adapted from a Mercedes-Benz all-terrain truck called the Unimog, the vehicle was equipped with videoconferencing equipment and a 40-foot mast with a camera that allowed passengers to see the terrain ahead. (An attachable trailer, meanwhile, featured a collapsible sleeping loft and an espresso machine.) A combination of rugged pragmatism and sleek design, the MaxiMog was eventually displayed at the New York Museum of Modern Art.

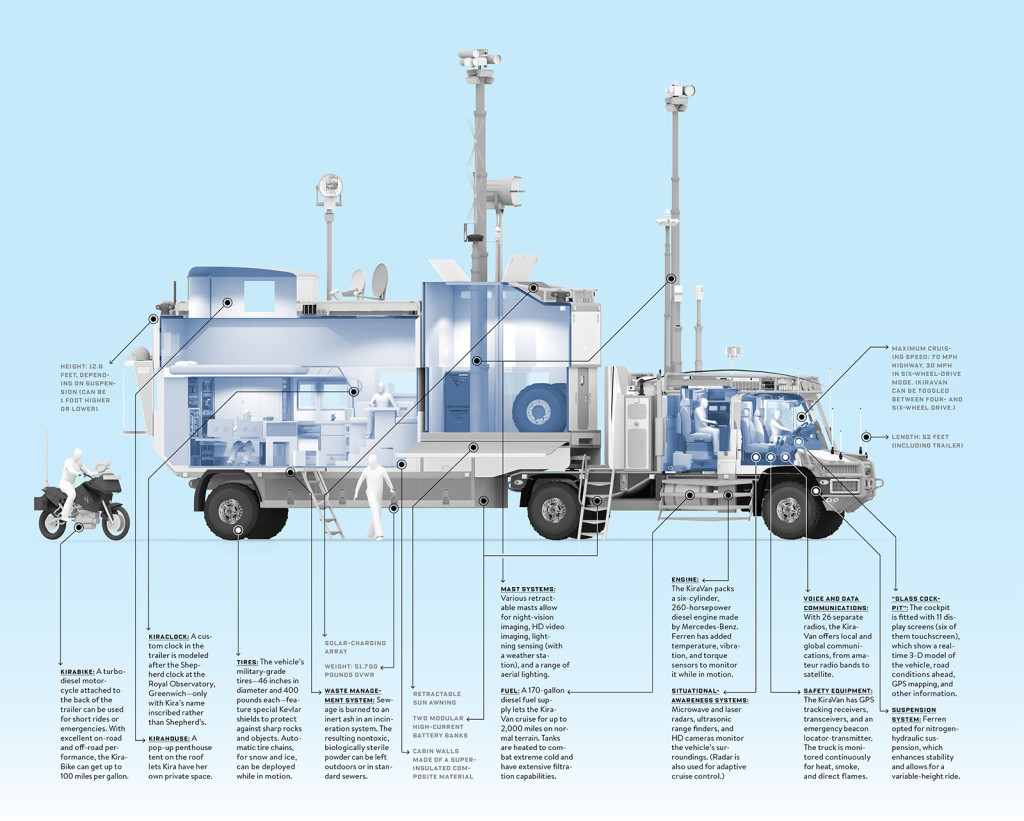

Around the time Kira was born, Ferren had an idea. What if he built an all-new, bigger and better expedition vehicle? No, more than that, what if he made theultimate adventure truck, the very platonic ideal of such a thing—which he could outfit for a family of three? He started to envision a vehicle that could take Kira nearly anywhere on earth without limitation—a mix of high-powered machinery, bomb-shelter self-sufficiency, and luxe-life accoutrements. It would be a mobile, malleable five-star fortress. It could form the centerpiece of his and Kira’s exploration of the world and be her ride into the future. Before he drew up the first blueprints, he’d given it a name: the KiraVan.

Ferren then set out to build the thing, which required dealing with all manner of complicated questions. For example: What materials could he use that would endure both extreme cold and extreme heat? “You’d think it’d be harder to design a jet than an off-road car,” he says. “You’d be wrong. It actually gives you an appreciation for why there are so many shitty cars and why there are so few great anythings. Because, it turns out, to do a great thing is hard.”

To answer the hundreds of questions nagging at him in his quest to build a supertruck, Ferren traveled all over the globe to seek the advice of experts. He spoke with mining consultants to learn how their equipment survives harsh conditions. He picked the brains of oil explorers to find out how their machinery functions over difficult terrain.

Now, nearly four years later, it is almost, sorta, kinda finished, and while Ferren won’t divulge the exact budget of the truck, he grants that its total cost is in the millions. If Ferren’s claims are to be believed, when it finally hits the road sometime this year it will be the most elaborate all-terrain vehicle ever built—a six-wheeled terrestrial spaceship capable of traversing nearly any terrain, from mud-swamped roads to rock-covered pathways to small bodies of water. It will be able to travel up to 2,000 miles without resupply and navigate slopes as steep as 45 degrees—an incline that is difficult to walk up.

Then there are the extras, which include Kevlar-reinforced tires, more than a dozen interlocking communication systems, and a diesel-powered motorcycle “dinghy.” Add to that the KiraVan’s massive trailer, which is 31 feet long and more than 10 feet high and houses an ecofriendly bathroom, a custom-designed upscale kitchen, and Kira’s own “penthouse” loft (which she herself helped design). The only thing missing is a built-in espresso machine. A countertop one will have to do.

Because of his considerable intellectual and financial resources, Ferren can pursue his vision without regard to the usual constraints of time, money, or manpower. And he has. “Bran can go overboard,” says a good friend, former Microsoft CTO Nathan Myhrvold. “Actually, for him, overboard is normal.” In fact, Ferren’s truck is a lot like Ferren himself: unapologetically audacious, highly adaptable, and more than a little extreme.

Ferren, it should be noted, is not especially particular about cars. When we first meet, he picks me up at an East Hampton train station in his 1986 Mercedes 300E, which is strewn with Kira’s Cheerios and takes a bit of coaxing to start up. “I’m of the old ‘buy it and run it into the ground’ school,” he says. “I’m as appreciative as the next person when I see a remarkable Bugatti. And I certainly admire what various designers and engineers have been able to accomplish. But that doesn’t make me a car guy.”

Ferren spent his early childhood in Manhattan before his family relocated to its East Hampton property, parts of which were originally owned by Jackson Pollock. He grew up surrounded by engineers—one of his uncles worked as a flight-test director for North American Rockwell—and artists. His mother, Rae Ferren, who still lives on the property, is a renowned impressionist painter, while his father, famed abstract expressionist John Ferren, was a contemporary and friend of Pollock and Pablo Picasso; some of John’s work is now part of the Guggenheim permanent collection. “My father had several very distinctly different periods of painting,” Ferren says. “Some were geometric, some much more free-form. Watching him gave me at least a set of examples on which to base my own behaviors.”

Growing up, Ferren would take apart surplus electronic equipment and furniture, trying to learn how they were built before eventually working on his own creations. One early invention was a robot he constructed for a high school talent show, which promptly (and intentionally) exploded when it came onto the stage. Ferren left before graduating, though he still wound up getting accepted into MIT—from which he promptly dropped out after a year.

In the ’70s, following a stint in summer-stock theater—he performed onstage and worked on lighting design—Ferren was recruited to create shows for rock groups like Emerson, Lake & Palmer. That led to Broadway shows like 1978′s Crucifer of Blood, a Sherlock Holmes tale for which Ferren used rumbling ultralow-frequency speakers and lightninglike strobe effects to give the audience the impression that a storm was actually brewing outside. “That was one thing I learned in theater,” Ferren says. “How you use theatricality and timing to do something that peoplethink they understand but really don’t.”

Soon Ferren had his own firm, cheekily named Associates & Ferren, and was getting big gigs in Hollywood, creating hyper-sensory visuals for the trippy 1980 sci-fi drama Altered States and whimsical special effects for the 1986 remake ofLittle Shop of Horrors (the latter earned Ferren an Oscar nomination). But he could never settle on just one thing, and between movie gigs he found time to work on projects ranging from specially filtered sunglasses to robot-controlled TV cameras to visual effects for a Paul McCartney tour. “He’s so knowledgeable about so many things that, at some point after meeting him, most people think, is this guy a bullshitter?” Myhrvold says. “But he really is that smart.” As Ferren and I cruise through the reliably psychotic Hamptons midday traffic, he adds, “There are people who are craftsmen, who really like doing the same thing over and over again. I’m not like that at all. To me, it’s ‘come up with a new idea nobody’s seen before, get it going enough to prove the point, and then get on with the next.’”

In the late ’80s, a friend of Ferren’s introduced him to Robyn Low, a professional chef. Ferren hired her to consult on a kitchen he was building. “He asked me out, and I said, ‘No, I don’t date clients,’” Low remembers. “And he said, ‘Fine, you’re fired.’ And then we were off.” The two never married but have been together since.

By the early ’90s, Associates & Ferren’s client list was dominated increasingly by one name: Disney. In fact, Ferren would work on so many projects for the company that in 1993 it bought out his firm for an undisclosed sum and relocated Ferren to the West Coast, eventually making him president of research and development in the company’s Imagineering department. “His job,” then-CEO Michael Eisner says, “was to attack individual problems, like finding out how to make an elevator free-fall faster than gravity.”

For that assignment, used in the Tower of Terror ride, Ferren and his team developed their own elevator system that could move at different drop speeds. Other big-scope assignments followed, like ABC’s Times Square television studio—which required then-complex LED screens and blastproof glass—and the high-speed General Motors Test Track ride at Epcot Center. “He was the instrument of change and creativity and craziness,” Eisner says. “What the Imagineers did was really an extension of what Walt Disney did, which was find a way to take technology and layer it with entertainment. And Bran was brilliant at that.”

During his tenure at the company, Ferren created the Disney Fellows program, which brought in technologists, engineers, and even astronauts to work as in-house advisers. One of his first hires was Danny Hillis, a pioneer in the field of parallel supercomputing; the two hit it off, and in 2000 they left Disney to start Applied Minds.

The company quickly acquired a reputation as a sort of military-industrial toy shop. Visit its five-building Glendale, California, compound and it’s easy to see why. To enter you must step into a cherry-red English phone booth and pick up the receiver; suddenly a door opens and you’re inside an office that leads to a flotilla of workstations and machine shops. In one room, there’s a full-scale military command center mock-up, in another an immersive, real-time digital-imagery dome that uses 50 projectors to create a crisp, zoomable image of anything from satellite images to 3-D renderings. It’s the kind of place where you trip over a robot on the way to the bathroom.

Applied Minds proved to be the ideal playground for Ferren’s various creative compulsions—design, engineering, even old-fashioned showbiz razzle-dazzle. And it gave him the resources to dream bigger and crazier than ever before—not that he’d really ever reined himself in.

Zpocalypse Lunch

MPV 1/18 – 1/25

Ave. 37 miles per day @ 18.89 MPG

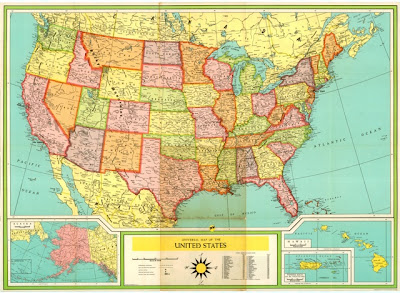

Silence of the Maps

I have several poster sized prints that I had scanned earlier this week, one was a 1960s map of the US that i found at a flea market. I like the colors and the general patina of a 50 year old document. Bizarre coincidence, I was watching Silence of the Lambs on Netflix and what does Jody Foster creep by before the lights go out in Buffalo Bills basement? THE EXACT SAME MAP!