The Art of Making People Go Away

— January 6th, 2015

You probably don’t think much about “Do Not Disturb” signs at hotels, unless the maid rudely barges in as you sleep. Then you think, “Hey, didn’t you see the door hanger? What happened to that?” But when you look through Edoardo Flores’ collection of just over 8,700 Do Not Disturb signs from 190 countries around the world—which he documents on Flickr—you’ll find they can be quite beautiful and revelatory. So-called “DND signs” tell you a lot about the character and mores of the places you find them.

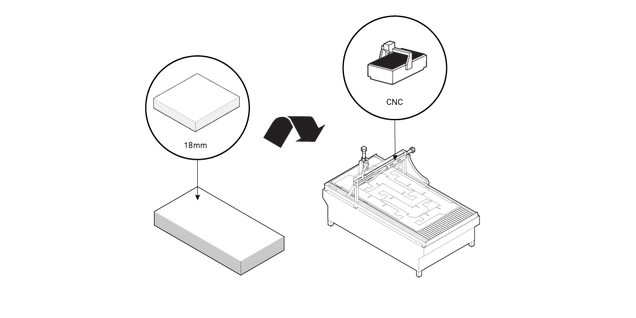

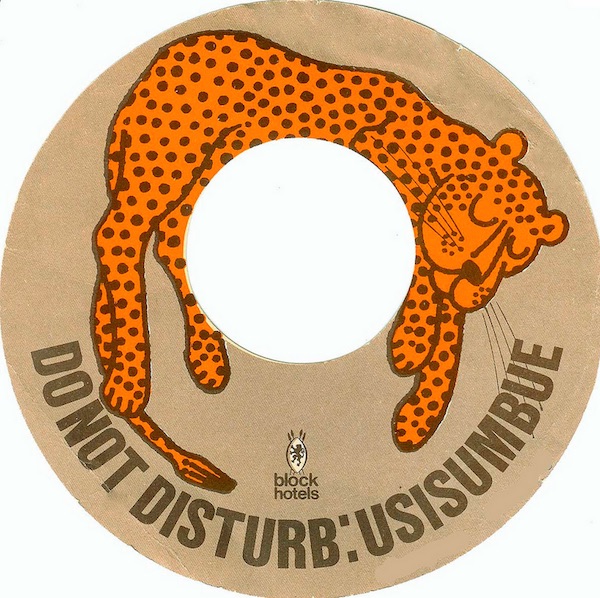

Images of sleeping, snoring “Zs,” and shushing (“shush” is spelled “chut” in France) appear all over the world. Images indicating “stop” or slashes over maid figures are quite common. In places where the labor for handicrafts is cheap, resorts often feature individual handmade wood or metalwork pieces for their Do Not Disturb signs. Other hotels revel in the fantasy that brought the tourists in the first place—dreams of an exotic world or animals that populate it. The door hangers for hotels in English-speaking countries tend to be made of paper and feature cheeky slogans and phrases instead of plain ol’ “Do Not Disturb.” In certain cities, like Las Vegas, it seems more acceptable to make it explicit that sex—and possibly paid sex—is a reason for keeping the door closed.

A retired training specialist with the International Labor Organization of the United Nations, Flores, who lives in Italy, had the good fortune to spend his 32-year career traveling to places like Bhutan, Iraq, Burma, Pakistan, and Fiji. However, it wasn’t until 1991, when he was nearly 50 years old, that he started keeping the Do Not Disturb signs he encountered on his stays.

“Do Not Disturb signs have been known for covering up crimes, or at least, delaying the discovery.”

“I think most collections start by chance,” Flores tells me over email. “I happened to travel quite a lot for work and stayed in many differenthotels. I picked up a first door hanger from a hotel in Islamabad, Pakistan, as a souvenir. Someone back at the office saw it and suggested it would make a nice collection, so I started picking up more on my other trips.

“Before that, I had started keeping spoons with airline logos/names from some of my flights, and although I have several hundred, it never took off as a collection,” he continues. “I also have hundreds of toilet seat bands from hotels. Some of them are quite interesting, but these, too, are not a formal collection. Finally, I more recently started collecting hotel key cards (the magnetic ones), and I already have several thousands.”

At this point, Flores is only one of a handful of serious Do Not Disturb collectors—including three adults in Germany, Switzerland, and Thailand, and a 13-year-old Canadian girl in Hong Kong—and he ranks himself No. 3 among them. They’ve all become friends and make a point to meet from time to time. The “Hotel ‘Do Not Disturb’ Sign Collectors” Facebook group currently has 107 members, but Flores says most of them are not serious collectors.

Even though he has traveled extensively, Flores hasn’t been to all of the countries he gathered DND signs from. “I have bought some on eBay, but not many,” he says. “I have often searched flea markets but found nothing. I receive many donations from friends, colleagues, and even complete strangers who travel for business or pleasure, but most of my signs come from exchanges with other collectors. I have also contacted hotels directly, but the response has not been encouraging.”

Hotel chains like Hilton, Sheraton, Radisson, and Holiday Inn often use variations of the same door hangers all over the world. While they do change their signs occasionally, Flores says the difference is often subtle. When he travels now, Flores tries to stay in a place he suspects will have something special, “but it’s always a gamble.”

However, he doesn’t necessarily have to check in to the ritziest joints to find amazing signs. “Strangely, many of the most expensive and exclusive hotels sometimes use very plain and unattractive signs,” Flores says. “On some occasions the price of the room correlates with how elaborate the sign is, mostly in Asian countries like Thailand, Indonesia, Laos, Cambodia, and Myanmar.”

And before Flores puts the Do Not Disturb sign in his bag, he considers how valuable it is. “Some of the more common paper ones are no loss to the hotels, so I just take them,” he says. “Other more elaborate or special ones like the wooden ones, I ask to buy them from the hotels. These are all individual, handcrafted pieces. Even though they’re usually found in countries where handicrafts are common and cheap, when hotels agree to sell these signs, they ask for quite a lot of money.”

Prior to Do Not Disturb signs, hotel staff just followed the clock, and maids knocked and walked in on people sleeping, showering, or engaging in other private bedroom activities. While they’ve done extensive research, Flores and his DND collector friends haven’t been able to nail down how or when the sign-hanging tradition began.

“The first widespread use was probably in the beginning of the 20th century, mostly in the U.S., in some of the more prestigious hotels where discretion was the better part of valor,” he says. “DND signs have also been known for covering up crimes, or at least, delaying the discovery.”

Do Not Disturb signs are most commonly made out of paper or card stock—they either hang on the door knob or insert into the electric lock. Some are die-cut into shapes like locks, keys, animals, or seashells. In places where the door opens to the outside, the Do Not Disturb sign may be a small sand bag that hangs on the door knob by a rope. While many DND signs have a “make-up room” message on the back, not all do. Signs that have “Do Not Disturb” messaging in multiple languages can have hilarious errors.

Paper signs can feature gorgeous designs or silly comics. In the United Kingdom and the United States, the focus seems to be on wordplay or witty text, using phrases like “My bed is so comfortable that I’m still in it,” “Beauty sleep in progress,” “Leave me alone,” “Taking a post-lobster buffet nap,” “Constructing a pillow fort,” or “Go away.” For example, a door hanger for Clarion Hotels, part of the Choice Hotels group in the U.S., gives a checklist of reasons “Why I Can’t Be Disturbed.” The list includes being tired from food, exercise, and business, but the option that’s already checked is “I’m trying to call myself on the two-line phone while surfing the Internet in my underwear.”

The boldest DND signs simply say, “Don’t” or “No.” More polite signs say things like “Privacy Please.” “Quite a number of hotels seem to pay a lot of attention to these humble accessories,” Flores says, “much to the collector’s delight.”

Since 1997, the Rufflets Country House Hotel in St. Andrews, Scotland, has been using a teddy bearnamed Rufus as a Do Not Disturb sign. If the maids are given the signal to clean the room, Rufus is placed among the guest’s things, like sitting at a laptop. The hotel considered getting rid of this tradition in 2008, but in an online poll, guests voted overwhelmingly in favor of keeping the bears.

In Asia and parts of Central America, Do Not Disturb signs can be individual works of art, and these are among Flores’ favorites. Wood is hand-carved into monkeys, elephants, deities, or shushing humans, and sometimes even hand-painted. Pillows may be hand-embroidered. Metal is forged into faces with eyelid flaps that latch down to indicate sleeping, while other signs are woven by hand. One painted wood block from Thailand shows a surprisingly intimate scene of a young woman sleeping, her bare breasts popping out of a sash tied around her torso.

“For me, the country of origin is important,” Flores says. “I have a very unique piece from the Vatican City from the Domus Sanctae Marthae, which is the hotel where the current Pope lives. I also love some very simple handmade pieces from Pacific Island states such as Kiribati. I’m desperately looking for pieces from non-tourist countries such as Somalia and North Korea.

“Quite a number of hotels seem to pay a lot of attention to these humble accessories—much to the collector’s delight.”

“I also collect DND signs from cruise ships, which I consider floating hotels, and the adhesive-label type found in airline amenity kits, mostly in business class—I consider these seats flying hotel rooms.”

Some Do Not Disturb signs serve a double-duty, advertising credit cards, rental cars, theater shows, restaurants, tourist attractions, or even perfume, like Chanel No. 5. A door hanger for a hotel in Kenya, for example, promotes Safari boots, which you’d obviously need if you planned to go stomping around with lions.

Aside from the hand-painted signs, Flores enjoys the cartoons on older signs from countries like the U.S., Italy, Spain, and Portugal. “A very nice piece I got recently from the InterContinental Westminster in London shows a caricature of the former Prime Minister Margaret Thatcher cleaning the room.”

If Margaret Thatcher were cleaning the room, I’d say that would be a sight worth the intrusion. But while she’s stacking fresh towels don’t forget to slip that Do Not Disturb hanger into your suitcase.